In The Smuggler’s Gambit, 17-year-old Adam Fletcher is the son of a young, single mother in a port town in 1765 North Carolina.

When he finds himself in trouble with the law, he is forced into an apprenticeship to avoid a harsher criminal punishment. As events unfold in his new life with a local shipping merchant as his master, Adam soon finds himself caught in the middle of a smuggling war.

The decisions he’s forced to make question his loyalties, his honor, his courage and ultimately his will to survive.

How real life intersects with The Smuggler’s Gambit

It’s as though Arthur Butler had no history before that fateful Saturday on the seventh of April 1764.

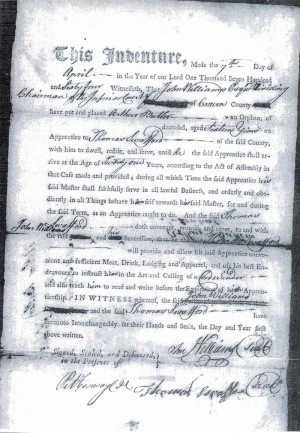

In fact, the first piece of documentary evidence of my fifth great-grandfather’s life was his apprenticeship bond. At age 16, he appeared in the Craven County magistrate’s office where he was made an apprentice to a rigid man who lived in Swift Creek named Thomas Swafford.

Swafford wasn’t from Swift Creek. In fact, he was a lapsed Quaker who had come into the North Carolina colony from Pennsylvania when he was younger.

It was uncovering these evidences, and the ones that followed, that ultimately led me to write The Smuggler’s Gambit.

Arthur’s father had been a shoemaker, I think. A lot of the boys in the Butler family were — at least it appears that way from looking at Butler estate records in the surrounding counties.

But Arthur, well, he was a bit of a mystery.

I was delighted when I first found his apprenticeship bond in the Craven County records, but my joy was quickly turned to sadness when I saw that just four years later, in June 1768, Arthur returned to the Craven County court to complain about his master:

Arthur Butler complains that Thomas Swaffer [Swafford?] is keeping him at servile labor and not teaching him to be a cordwinder.”

By September, the Craven County authorities intervened on my ancestor’s behalf:

Ordered that Arthur BUTLER formerly Bound apprentice to Thomas Swaffer be discharged from his Indentures it appearing to the Court that the said Arthur hath not been treated as an apprentice Ought to be, And that he be bound to Charles ROACH untill he arrive to Twenty One Years to Learn the Shoemakers Trade.”

More questions than answers

Was my ancestor being abused? The ‘servile labor’ mentioned indicates he was being used like a servant and wasn’t being taught the trade. He was less than a year from the end of his apprenticeship when he made his complaint to the court. How long had this been going on? What made things get so desperate that he finally went forward to have his apprenticeship changed?

Why was he made an apprentice at the age of 16 in the first place? His apprenticeship bond doesn’t name any parents, even though they usually named at least the father or mother.

Was Arthur an orphan? Or was he one of the misfortunate children of a single mother who was forcibly taken by the county and placed into an apprenticeship?

After nearly a decade of research, I’ve never been able to satisfactorily answer those questions about my ancestor’s origins, although I did learn what came after his apprenticeship was transferred and how things turned out for him in his life.

He ended up marrying the beautiful daughter of a wealthy, local landowner and county court justice, he served in the American Revolution, and they had several children. It was a true rags to riches story,

In fact, several years ago, I began working on a novel that was loosely based on the life of Arthur Butler. I worked on it on and off until early 2014, but finally abandoned it when I realized what I was writing was more of his biography than it was a novel.

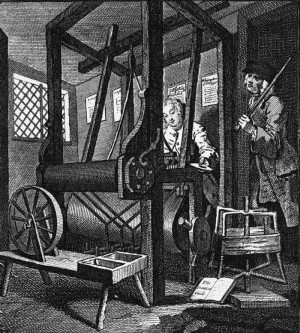

Nevertheless, the whole concept of apprenticeships really caught my attention.

I ended up coming up with an idea that combined both the elements of what was happening in America at the time my ancestor was apprenticed, along with some local history and information I knew about several of my other colonial-era ancestors and their associates, and the result was The Smuggler’s Gambit.

Forced Apprenticeships

Growing up, I always just thought about an apprenticeship as a means for a young person to learn a trade. It was the way things were done.

What I did not realize, however, at least not until I started researching apprenticeships in colonial North Carolina, is that often, apprenticeships were a forced enterprise.

In 1762, the law in North Carolina stated the following:

Where the estate of an orphan shall be of so small value that no person will educate and maintain him or her for the profits thereof, such orphan shall, by direction of the court, be bound apprentice, every male to some tradesman, merchant, mariner or other person approved by the court, until he shall attain to the age of twenty one years, and every female to some suitable employment, till her age of eighteen years; and also such court may, in like manner, bind apprentice all free base-born children, and every such female child, being a mulatto or mustee, until she shall attain the age of twenty one years: And the master or mistress of every such apprentice shall find and provide for him or her diet, clothes, lodging and accommodations, fit and necessary; and shall teach, or cause him or her to be taught to read and write; and at the expiration of his or her apprenticeship, shall pay every such apprentice the like allowance as is by law appointed for servants by indenture or custom, and on refusal shall be compelled thereto in like manner; and if upon complaint made to the inferior court of pleas and quarter sessions, it shall appear that any such apprentice is ill used, or not taught the trade, profession or employment to which he or she was bound, it shall be lawful for such court to remove and bind him or her to such other person or persons as they shall think fit.

In other words, if a child was orphaned (and an orphan was typically considered a child without a father, regardless of whether or not the mother was still living) regardless of ethnicity, or if they were ‘base-born’, or female mixed-ethnicity children, they were to be bound out, no matter what.

Just to be clear, here are what those old genealogical terms mean:

Base Born – An “illegitimate” child. (A child whose parents are not married.)

Mulatto – A person with mixed parents — black and white, although at times may have indicated black and Indian.

Mustee – A person with mixed parents — Indian and white. (Short for “mestizo,” the Spanish term for children of one Indian and one white parent.)

The colonies didn’t pass these laws out of cruelty, although the end results might have sometimes been cruel, nonetheless.

The practical reasoning behind the law was two-fold: First, to ensure that children who might otherwise not have someone teach them, be bound to a master and taught an industrious trade whereby they could enjoy a successful future. By learning to be self-sufficient, they wouldn’t become a burden on the colonies.

Second, the apprenticeship system provided a cheap labor-force for businesses. It was thought to be a mutually beneficial arrangement since the apprentice would be housed, clothed, fed and trained in a profession while the master enjoyed having an otherwise unpaid worker who lived on the premises and had to work how and when he was told.

Some people were bound from the time they were very small, in which case it could almost be compared to an adoption more than just an apprenticeship. Others weren’t bound out until they were teenagers.

Issues of Illegitimacy

I’m unfamiliar with laws from other colonies relating to unmarried women having children, but in North Carolina, ‘bastardy bonds’ were issued.

According to this website:

These bonds were intended to protect the county or parish from the expense of raising the child. When the pregnancy of a woman or birth of a child was brought to the attention of the court, a warrant was issued and the woman brought into Court. She was examined under oath and asked to declare the name of the child’s father. The ‘reputed’ father was then served a warrant and required to post bond. If the woman refused to name the father, she, her father or some other interested party would post the bond. In some cases, the mother and reputed father together posted the bond. If the woman refused to post bond or declare the father, she was often sent to jail.”

Illegimate children, or children whose fathers were not present, were always placed in forced apprenticeships unless someone in the mother’s family or circle of friends was willing to post a bond for the said child and act as surety for their welfare and upbringing.

In The Smuggler’s Gambit, Adam’s grandfather-figure and owner of the Topsail Tavern, Valentine Hodges, had stepped in as surety for Adam’s mother, Mary, since his father was not around. But when Adam ran afoul of the law, the county magistrate wouldn’t even consider allowing him to be apprenticed to Valentine. Colonial authorities didn’t see taverns as morally upright places, so some apprentice bonds would actually go so far as to forbid the youngster from visiting taverns or public houses. That was a very real worry for Adam when he was told he’d be made an apprentice.