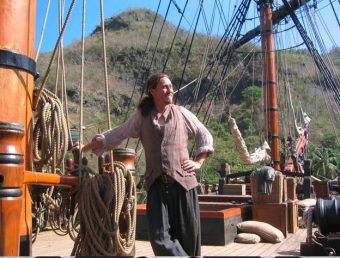

Courtney Andersen is the Historic Ship Rigging Supervisor at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park, but in addition to that, he’s also had some pretty cool gigs working on some projects you will definitely recognize (that picture with Capt. Jack Sparrow is a hint…). I’m also thrilled to report that Andersen has agreed to be a historic ships consultant for the Adam Fletcher Series. His first turn at providing advice for that has been for the soon-to-be-released fifth book in the series, The Stolen Bride.

Tell me a little bit about yourself. Where are you from originally?

I was born in Minnesota but moved down south when I was seven, first to the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, then Florida, Savannah, and back to Florida. I was always around water. When we lived in Minnesota my mom would take me down to the Mississippi River. We drove down to New Orleans following the Great River Road each year. We always stayed in Hannibal, Missouri on those trips, because I was fascinated with Tom Sawyer. I read Tom Sawyer, and Huckleberry Finn, and Twain’s Life on the Mississippi by the time I was nine.

Like Tom and Huck, I hoped that I could grow up to be a pirate.

What got you interested in ships and maritime history?

Living on the Gulf, and going to New Orleans, one of my first heroes was Jean Laffitte, the “pirate of Barataria”. By the time I was living in Savannah (where there is a great old restaurant and bar called The Pirate’s House, with underground tunnels that lead down to the riverfront for shanghaiing sailors) I was reading lots of pirate and sailing ship history. It was really exciting to live in places where some of the events took place. New Orleans and old Savannah gave me a real appreciation for historical buildings and the atmosphere they give, walking through old cobblestone streets that haven’t changed much in 200 years.

I went to the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida, originally to be a marine biologist. The replica of the Bounty from the 1965 movie Mutiny on the Bounty was docked in Miami, and I went aboard and begged for a job. I was a tour guide. The ship went out for cruises on occasion around the harbor, and being aboard her during those trips was a wonderful experience.

Eventually I started helping out the rigger on board, tending lines for him and eventually going aloft on the masts to assist. He taught me to splice rope. After work, I’d go to the library at the University, and read books like Darcy Lever’s Young Sea Officer’s Sheet Anchor, a guide for rigging a sailing ship step by step that was written in the early 1800’s, then compare what I had read with what was on the ship the next day.

Since then, rigging has always fascinated me. I spent the summer of 1991 sailing on Bounty from Miami up to New England, travelling from port to port in New York, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. A few years later, I started working on the replica of the Half Moon (d’Halve Maen), a recreation of Henry Hudson’s Dutch ship of exploration of 1609.

I worked with another ship rigger and honed my skills that first winter. I became the boatswain and occasionally mate on board, in charge of rigging up the ship in the spring, getting sails and yards and topmasts up, directing the crew in all their work, organizing raising and setting the anchor, handling the small boat, dealing with engine and generator problems, painting, varnishing, and bringing down all the yards and sails and gear for the winter. I did that work for seven years, and also spent a lot of time researching Dutch rigging of the 17th century, in museums in the US, Britain, and the Netherlands. There is always more to learn.

You mentioned to me that you’ve been involved with the beloved Pirates of the Caribbean movies. How did you wind up working on those?

One day, completely out of the blue, I received a phone call that I thought at first was a prank. The guy on the other end said he was calling from Disney, that they were doing a movie based on the Pirates of the Caribbean theme park ride, and they needed a rigger to design and build the sailing ship rigs. They had asked around, and my name came up a couple of times.

At first I said no, I wasn’t interested. They asked if I could come out to LA for a couple of weeks to get them going in the right direction, which I agreed to do. It was so much fun and so full of creativity and energy that I stayed to do the whole film. I had worked for a couple of weeks the year before on Master and Commander, working for a friend of mine; from that experience I learned a lot of what to do and what not to do in transferring traditional rigging to the world of movies.

What was your job on the film?

I worked for the Art Department. They gave me drawings of the ship hulls that they wanted to use, with all the decoration and elements that make the Black Pearl so unique, for instance. I took the time period and style and nationality of vessel, and drew up a rigging plan based on those criteria, with everything in the proper proportion.

The Art Director and Production Designer and Director would look at the plans, give me their feedback, and then I’d prepare a budget for what building the rig was going to cost. I hired a crew of four riggers, mostly friends of mine from other ships, and we set to work in LA, first building the Dauntless (basically a 3/4 scale HMS Victory), then the Black Pearl on stage.

We flew down to St Vincent in the Caribbean and built another Black Pearl, as well as all sorts of other boats and ships and parts of ships, for masts that fall and cross between ships, set dressing pieces and special effects gags.

Ok… In my mind, I now know that you’re the guy responsible for helping perfect the scene that made Capt. Jack Sparrow look so cool — right off the bat — in the first POTC film. Tell us about that.

One day the Art Director asked me how tall I was and what I weighed. When I told him, he looked at me and said, “Yeah, that’s what Johnny [Depp] says too.” He told me to go meet with Special Effects out at the set and work with them on the sinking boat gag. Yes, I was the guinea pig for perfecting the great scene in the movie when Capt. Jack stands on the yard of the little boat (we called it the Jolly Mon) and it sinks under him, timing it perfectly for him to step off and right onto the dock.

I must have done that ride a dozen times before it stopped falling over and dunking me in the water. Finally on the first day I met Johnny Depp on set, he stood on the dock and I stood on the yard of the little boat, and he watched me ride it down and step off onto the dock next to him. I helped him get on the yard of the boat and showed him what to hold on to, and then he did the stunt — with a bit more flair than I had done.

Without a doubt, that is one of the most memorable scenes in any of those movies, so let me just say, “Well done, sir.” What other sorts of things did you end up doing?

One of the main jobs I had on the movies when we were shooting was to stay close to the director on set; he would say “Can that rope move?” or “Can you show those actors how to haul a line?” or “What jobs would the background people do?” Basically, I’d be there to work with any part of the rig for whatever the director wanted to see, and give suggestions to the actors for “shippy” things to do.

The actors were all around there as well (think of the director’s chairs set up with everyone’s name on them…that’s really what they are for), and everyone was very friendly. Johnny would ask questions about what it was like to sail on an old sailing ship, or talk about missing his kids, or we would commiserate about getting the runs from the food at the restaurant we had both happened to eat at the night before.

How many films in the series did you work on on? And did your work on the films allow you to meet or work with any of the other principle actors or production staff?

I ended up working on all five of the Pirates movies, and working with the actors and crews were like a family.

Mostly the same people worked on the first three movies, with fewer doing the 4th. By the time we did the 5th, there was just a handful of the crew who had done the others. Johnny Depp, Geoffrey Rush [Capt. Barbossa], and the two who played Murtogg and Mulroy, the Marines-turned-pirate, were all there, and it was great to see and hang out with them again.

Have you worked on any other films since then?

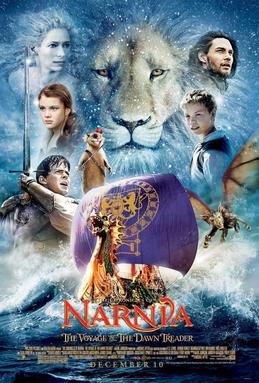

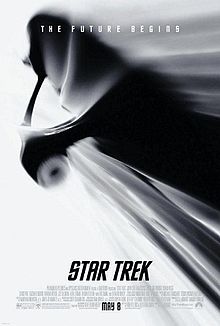

That movie work led to other jobs, doing rigging design for motion pictures: National Treasure, Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 12 Years a Slave, as well as some that never made it to production. Oh, and J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek.

I know your career in historic ship rigging has been about a lot more than just film work. What other projects have you been especially proud of?

Some other projects I’ve been a part of include pulling the masts of the Golden Hinde replica in London, to get them in shape for the Queen’s Jubilee a few years ago…that was pretty awesome, to be on the Thames, working on the Golden Hinde (the original was sailed under the first Queen Elizabeth).

I am scheduled to do some rigging overhaul on the Nonsuch, a replica of a 1650’s vessel which is inside the Manitoba Museum. This month, I am building new shrouds for the USS Maine Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery as part of the restoration of the memorial to the ship and crew blown up in Havana harbor in 1898.

I work full time at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park as the Historic Ship Rigging Supervisor. We just sent our 1886 steel sailing ship Balclutha to dry dock, and are going to continue rigging the 1895 West Coast lumber schooner C.A. Thayer. I spent nearly six years researching and designing her rig, to return her to what she looked like when she was first launched.

What is your favorite era of maritime history, or what era fascinates you the most?

I really love the whole range of the age of sail, from the 1500’s and the ships of exploration and colonization right up through the Victorian period as sail gave way to steam. I just built a model of a little “cog” from the 1400’s, so I did a bunch of research on those late medieval ships and sailors. It’s fascinating to see how vessels evolved, and how the techniques of navigation and rigging and shipbuilding developed and allowed people to sail further and further. There’s a romance about the sea, and getting away from land.

Was ship construction and sailing much different between, say, the Golden Age of Piracy and the period of the Adam Fletcher books (1760s)? And now that I think about it, what about the Roanoke Voyages/Jamestown era versus the GAoP?

Ships like those at Jamestown or Manteo are really the same as the Golden Hinde and Half Moon and San Salvador and even Kalmar Nyckel or Batavia. That’s a span of about a hundred years, from the early 1500’s to the early 1600’s. There were some changes after the late 1600’s, such as the introduction of the ship’s wheel, and the phasing out of the spritsail topmast, and the lowering of the high poop and forecastle.

Rigging lines evolved a little, but really, sails and ships were handled the same way they had been from the 1400’s through the early 1900’s. Masts got taller and as they did, additional sails were added. But a sailor from Columbus’ day would recognize every line on the Balclutha here at SF Maritime.

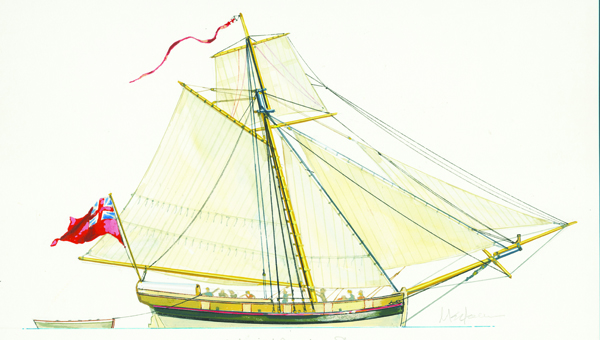

Chapelle’s History of American Sailing Ships has some good info for the 1760’s on the types of vessels around American waters, including ships, sloops, pinks, brigantines, shallops, ketches, barks, and schooners. He says that the bulk of the vessels were small, and mostly sloops from 25 to 70 tons, then brigantines from 20 to 150 tons. The book has some excellent plans and illustrations that show the size of these vessels.

Another excellent book is The Colonial Schooner 1763-1775 by Harold M. Hahn, with illustrations and photos of a model of the schooner Halifax, showing people working aboard and down in the hold. It gives a good idea of the scale of these small work vessels.

I think you mentioned to me you’ve been to Beaufort. Do you have any special insight you can offer into sailing and shipping on the North Carolina coast during that pre-Revolution period?

So, in Adam Fletcher’s day, you’d see ships still with a slightly raised quarterdeck and foredeck but possibly only a couple of steps up a ladder, not necessarily a full head-height cabin area; all the rigging would still be tarred hemp —not manilla — with very little metalwork used beyond hooks and chainplates, everything else was wood. Ships and boats in the Colonies were already showing some variations from their European roots. There were fast vessels being made, variously called “Bermuda” or “Jamaica” sloops, as well as the occasional three-masted ship.

It’s important to remember that true ships, larger three-masted vessels, were not nearly as common around the Colonial ports as smaller vessels, schooners, brigs, sloops, cutters, and even smaller boats. These were the primary coastal trading vessels; ships were more reserved for trans-oceanic commerce. That being said, even the sloops and schooners of 50′ or so would be sailed to the Caribbean and even farther.

There would likely have been a lot of vessels in the 35-55 foot range which had shallow enough draft to get over sandbars in the Outer Banks and up creeks, and large enough to go out the inlets to travel down to Savannah or Charleston, and up to Jamestown and Yorktown, Hampton Roads, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Connecticut, and Boston. Harbors were full of small boats, rowboats and little sprit or gaff rigged boats to ferry a couple of people from ship to shore or sell goods on a very small scale, or to ferry people across rivers or small bays, or engaged in fishing.

Small vessels called “lighters” were often used for offloading the cargo of a larger vessel if it couldn’t get to a dock or if the port had shallow water and the cargo vessel had to anchor out.

Some folks may know that the infamous Blackbeard ran one of his pirated ships, the frigate Queen Anne’s Revenge, aground near Beaufort Inlet. Based on what we know about the QAR‘s characteristics, would a ship like that have been able to sail in Taylor Creek, or would the water have been too shallow?

Taylor’s Creek channel today is a depth of 8.5 to 9 feet, which would have been about touching bottom for Queen Anne’s Revenge; besides, Taylor Creek is a very narrow waterway. A ship like QAR wouldn’t sail in there. They could have kedged their way up, rowing out anchors ahead of the ship and using the capstan to haul themselves up, but it would have been more likely QAR was heading either just behind Shackleford Banks or Bogue Banks, both of those have fairly decent “tongues” of deeper water behind them, which could have provided anchorages — of course, I’m looking at a modern chart, and trying to see if there are natural deep waters aside from the dredged channels. But remember, the theory is that Blackbeard intentionally had QAR run aground to disable her and disband his crew, so it seems he was intimately familiar with those waters, and knew right where to do it.

Regarding pirate “ships,” generally speaking, large ships of over 150 tons were not as commonly used by pirates — so the Black Pearl is a bit misleading! Ships that size are less maneuverable, and need deeper water.

Pirates liked to be able to duck into shallow areas — like behind the Outer Banks — to avoid detection by larger Navy vessels. Those Bermuda sloops were ideal, being fast, yet still capable of being ocean-going. Pirates would cram them full of guns and carry sometimes 60 or 100 men on those small vessels. Blackbeard had one, called Adventure, also the name of many pirates vessels — they didn’t seem to be very creative when it came to names. He ran aground even in that, as did the Navy sloop hunting him down, during Blackbeard’s final battle off Ocracoke.

Many pirates started out with just a few pirogues, basically low rowboats, for surprising their victims at night and taking over the ship before the crews knew what was happening.

I believe there is a Blackbeard story about an attack from a pirogue near Bath. [See his victim’s deposition in the NC Colonial Records.] They are related to the periaugers or perogues, which were sometimes a bit larger and carried sails, but the names are so similar and spelling was not very standardized, so it can be difficult to be sure which type of boat is really being talked about. The perogues in the south tended to be made canoe-fashion, from solid tree trunks, and big enough to carry thirty or more barrels of goods.

[Below is a short video on a colonial-style periauger that was constructed in North Carolina.]

Everybody who knows me knows I’m a massive history nerd. I’m also a huge fan of the POTC movies, so it made my day when I learned you were a fan of the Adam Fletcher novels! I guess I should ask at least one question about your thoughts on the series. Who is your favorite character and why?

Aside from Adam Fletcher, I really like several of your characters. Emmanuel has some great stories in his past. I’d love to read at some point about all Blackbeard’s old crew having one last adventure together.

But of course I am most intrigued by Rocksolanah “Laney” Martin! I’m interested to see where her relationship with Adam goes. Growing up in the south, I am also fond of Aunt Celie in Murder in the Marsh. I appreciate the characterization of her being a maternal figure, watching out for Laney and the Martin household, and I thought it was pretty sensitive the way you addressed her fear of the thought of “freedom.” Not to justify or excuse slavery, or to suggest that it was all a happy situation all around, but that scene really gave an insight into how it must have felt to be taken from your home to a completely different environment, and be somewhat adjusted to it, then be given the option of freedom and having to sort out your own way in that strange world.

[All images courtesy of Courtney Andersen unless otherwise noted.]