While doing book research, I came upon an interesting article that was reprinted in several different publications in the 18th century. It was only credited as being written by M. Duhamel from the Memoires de Trevoux.

I had no idea who M. Duhamel was, but after searching on Google, I learned his full name was Henri-Louise Duhamel du Monceaux (or Duhamel de Monceau), and he was a French physician, naval engineer, and botanist.

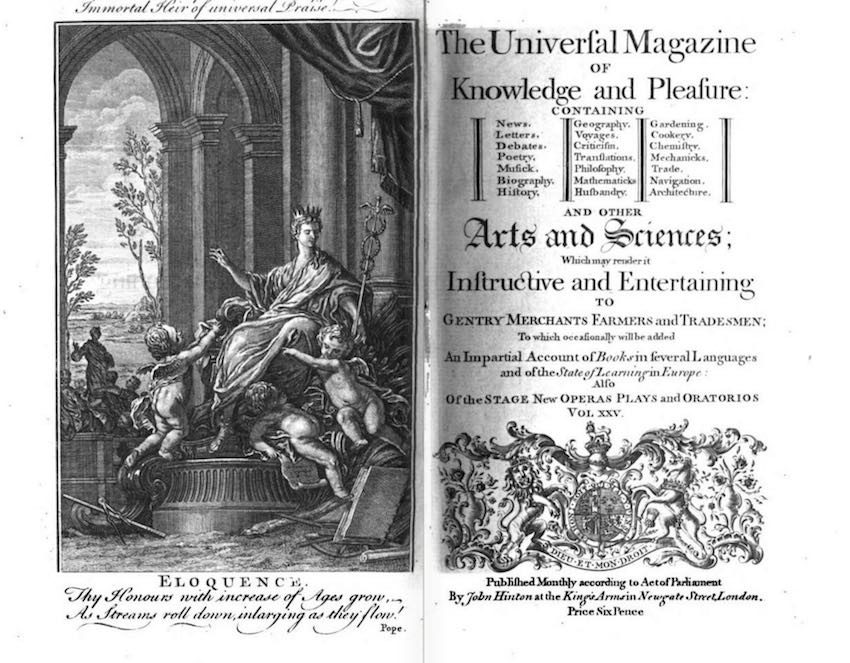

I found the article in the July 1759 edition of publication called The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure. The title page revealed more about the book’s contents (Just bear with me on this… It‘s interesting. I‘ll get to the part about “Preserving the Health of Seamen” just a little further down the page.):

Containing News, Letters, Debates, Poetry, Musick, Biography, History, Geography, Voyages, Criticism, Translations, Philosophy, Mathematicks, Husbandry, Gardening, Cookery, Chemistry, Mechanicks, Trade, Navigation, Architecture, and other Arts and Sciences; Which may render it Instructive and Entertaining to Gentry Merchants FArmers And Tradesmen; To which occasionally will be added An Impartial Account of Books in several Languages and of the State of Learning in Europe: Also of the Stage New Operas Plays and Oratorios Vol XXV”. Published Monthly according to Act of Parliament By John Hinton at the King’s Arms in Newgate Street, London. Price Six Pence.”

The article by Mr. Duhamel gave a series of tips for best preserving the health of a ship’s crew, including:

- Avoid anchoring in areas surrounded by “mud, marshes, and sheltered from the wind”

- Good air is everything. “Nothing but malignant vapours, or putrid exhalations in the air, can occasion those dreadful contagions that lay waste cities, and sometimes intire [sic] provinces.”

- Make sure the air can circulate. Stagnate air promotes disease.

- None should be permitted on board except for “fresh and healthy sailors” who possess “all necessaries in linen and cloaths to keep themselves clean.

- Keep the ship clean. Sweep, scrub, “especially on the inside, all the parts of the ship, and particularly the post of the sick and the cattle-fold.”

- All should be washed, but only during the heat of day. Heat helps dry that which has been washed.

- Vent as much as possible the air below decks.

- Vinegar! Use vinegar! Vapour of vinegar can be used, vinegar can be splashed on things, even just inhaling the “vapour” of vinegar can have healthful effects.

- The burning of sulfur can also be helpful, the vapours of which can be cleansing.

- “[T]he hold, where the air is more corrupt than in any other part of the ship, should never be the lodgment of the sick, except in the time of an engagement. He assigns them a place where there are no hatches from the hold nor the lower deck, because the air issuing from these places is almost always very unwholesome; and advises, in a particular manner, those that are in good health, to make no use of the wearing apparel and the hammocks of the sick, contagious maladies being chiefly communicated by cloathes.”

If you would like to read the full text of the article with Mr. Duhamel’s recommendations, I have transcribed it below.

An Account of M. DUHAMEL’s Method of preserving the Health of Seamen; from the Memoires de Trevoux.

WHENEVER we see the name of M. Duhanel prefixed to a book, we may be assured, that it is the fruit of the most ardent zeal for the advancement of useful arts, and the good of mankind. Such is his treatise on the Methods for preserving the Health of seafaring Men. It is a summary of what experience discovered to him as most advantageous in that respect ; and we shall therefore extract the most interesting points, and analyse the practical details.

After several observations on the difference of places whose situation is more or less wholesome, M. Duhamel concludes in general, that rising grounds, and exposed to the wind, are the most wholesome; that those situate near tide, fresh or fair water, are not subject to the epidemies that infect ships; that the sea is not the cause of these epidemies; that seamen are more exposed to them, when they anchor in roads surrounded by mud, marshes, and sheltered from the wind; that, when their health obliges them to go on shore, they should be compelled to return aboard for the night, or, if this cannot be conveniently effected, should be kept at a distance from marshy grounds, and not permitted ever to incamp or to lie without good tents set up in dry, high, and open places.

To discover the particular causes of infection in ships, M. Duhamel lays down this general principle: That the different qualities of the air, the vapours that humect, the exhalations that penetrate it, influence to a great degree, the health of the animals that breathe it. Nothing but malignant vapours, or putrid exhalations in the air, can occasion those dreadful contagions that lay waste cities, and sometimes intire provinces. The more the air is debarred of a free circulation, the more it is susceptible of impressions from the causes that alter and corrupt it. Now all these inconveniencies concur to infect the air in ships, especially in the hold of a ship. It there becomes thick, and its thickness does not permit the perspiration of animals that breathe it, to discuss and dissipate it. Whence it happens, that the warmth of this confined air is more sensible than that of the exterior air, and its elasticity is prodigiously weakened. It has not, therefore, that degree of condensation, that freshness, that motion, which makes it favourable to respiration. This may be evinced from the incidents that happen to a bird shut up under a bell, where the air it breathes cannot be renewed. Between decks, and in the hold of ships, provisions contract heat, ferment, and send for exhalations; of which the volume, stench, and malignity are augmented by the like produced by the dung of animals, the smell of their wool, their respiration and transpiration, and the vapours exhaled from the putrid water in ships and in the sink, and even by the bitumen exalted from the sea.

If the ship’s crew are attacked by any sickness, the causes for infecting the air are still more multiplied. During voyages into cold, and much more into hot countries, seamen meet with new sources of disorders. The changes of air and climate are the more dangerous by their indiscretion in braving and even provoking their pernicious impressions. Lastly, salt aliments, though less subject to corrupt, yet, by being hard of digestion, bring on a multiplicity of diseases, especially the scurvy. These are the enemies M. Duhamel endeavors to destroy.

He first proposes precautions against their attacks by preventing them, persuaded, that it is always easier to guard against diseases, than to cure them; or that, if they cannot be intirely avoided, their violence may, in a great measure, be checked or abated.

These precautions are:

- “To admit none aboard, but fresh and healthy sailors, and well provided with all necessaries in linen and cloaths to keep themselves clean. Sick, fatigued, ill-cloathed sailors are, in ships, a source of contagion.

- To clean frequently the sink; to sweep and scrub, especially on the inside, all the upper parts of the ship, and particularly the post of the sick and the cattle-fold. All should be carefully washed, but this ought to be only during the heat of the day, that it might dissipate the moisture before night. Cleanliness in the sailors, and keeping the ship from all filth, infection, and every thing productive of putrid exhalations and vapours, cannot be sufficiently attended to.

- To purify and renew, as much as possible, the air in the hold and under decks. For this purpose are used vent-holes, the wind-sleeve, bellows, and principally M. Hale’s ventilator.

Vent-holes are only apertures, through which the infected air may escape. Some observations are necessary to direct their use. Vapours are lighter than pure air, and their levity determines them to ascend through the vent given them. This is a general principle, that regulates the form and use of all the machines for reneweing the air of ships. Therefore the vents for introducing the pure air cannot be placed too low, nor those for letting out the infected vapours too high, and, if they were too narrow, the vapours would find in them a friction, which most obstruct, and could not be conquered by their levity. As to the other machines, M. Duhamel proposes some methods for making their play more easy, and their action more effectual.

Fire is another agent, which may serve the same purposes. It rarefies the ambient air, and the vapours it is loaded with. This rarefaction augments considerably their levity, and consequently accelerates their going out. Perfumes are also reckoned as a means for purifying the air of ships. The author alledges some examples of very troublesome and obstinate fainting fits, wherein the smell of vinegar alone produced the most salutary effects. This virtue he attributes less to the stimulating action of vinegar, than to the impression it produces on the air the sick persons breathe: For, says he, there are none but have found some pleasure in breathing the vapour of vinegar on days disposed for stormy weather; wherein, the air being less fit for respiration, one is obliged to fetch frequent and profound respirations; and thus it is sufficiently proved; that it is necessary to sprinkle good vinegar between the decks, and especially in the apartment of the sick. However, it seems probable that the effect is almost as transient as salutary; that is, that the salubrious quality communicated by vinegar to the air, is not so durable as the ease it procures the sick.

The vapours of burning sulphur, continues our author, hinder fermentation, and consequently corruption, even in the liquors that are most disposed to ferment, such as wine, bear, &c. It is also allowed that those vapours serve to disinfect the merchandise that come from countries suspected of contagion. Those Captains of ships are therefore to be commended, who from time to time burn priming powder steeped in vinegar between decks, or who perfume the decks with vinegar poured upon a red-hot ball. M. Duhamel prefers the aspersion of vinegar to its vapour, whereof the smoke is disagreeable, and may be hurtful, if too strong; for indeed the smell of vinegar is more grateful than breathing its vapour; andhe also counsels, in certain roads, when the weather is fair, to perfume with the vapour of sulphur the decks and bread-rooms. Care at the same time should be taken to guard against all accidnets of fire; and the ventilator of M. Hales, a bellows so powerful for pumping air, would not be less so, in diffusing the perfumes throughout all parts of the ship. If any disagreeable smell remained, it might be easily disippated by going about with a red hot iron ladle filled with aromatic drugs of little value, such as juniper-berries, and suchlike.

From all this practical doctrine M. Duhamel concludes, ‘That the hold, where the air is more corrupt than in any other part of the ship, should never be the lodgment of the sick, except in the time of an engagement. He assigns them a place where there are no hatches from the hold nor the lower deck, because the air issuing from these places is almost always very unwholesome; and advises, in a particular manner, those that are in good health, to make no use of the wearing apparel and the hammocks of the sick, contagious maladies being chiefly communicated by cloathes.’ In the time of a plague it has been observed, says he, that whole families have preserved themselves from the contagion, by shutting themselves up in their houses, though they received their provisions from infected persons, who sometimes fell dead whilst they conversed with them from their windows; whereas, at the same time, a single rag would communicate the plague. Of this, adds, he, I have a very decisive proof in the contagion that destroyed so great a number of cattle in France and elsewhere. One of our farmers prreserved all his cows, by keeping them shut up in a stable, and by hindering his domestics to go into infected stables, and those of his neighbours, whose cattle died, to come into his.

It is true, all these precautions for keeping ships from being infected are an addition to the seaman’s toil; but they need not be deemed such when found highly expedient for obtaining the great ends required from their service. M. Duhamel proposes likewise some substitutes to the ordinary food of seamen; but as the victualling of ships, particulary those of war, is provided for as the wisdom of a government thinks most proper we shall not here touch up that article.

When ships are arrived at their place of destination, M. Duhamel recommends that their stay should be as short as possible in rivers and muddy ports sheltered from the wind and known to be unwholesome. He also advises to avoid places wehre the sea is too calm; to abide only where there is good anchorage; to quit from time to time the road, and cruise about, in order to exercise the seamen; to place the land hospital far from vallies, marshes, and stagnant waters; to distribute preservatives against sickness to the soldiers, that repair at night to their tents; to furnish them with fresh provisions in fruits, pulse, fish, &c. This care will be particuarly necessary in the torrid zone: Cold countries require a peculiar treatment in cloathing, exercise, regimen &c. and sailors struck with cold should be kept from the use of spirituous liquors, till they are made to receive a certain degree of warmth.

To conclude, this work may, with good reason, be reputed an excellent manual for all sea-officers, who, no doubt, on perusing it, will confess the obligation they lie under to this learned Academician, for his zeal in promoting their interest, and preserving the lives of those committed to their charge.