On Adam Fletcher’s first day as an apprentice (in The Smuggler’s Gambit), he is placed under the instruction of Boaz Brooks, senior cooper and second-in-charge at the shipping company. Adam learns that Boaz was also forced into an apprenticeship when he was younger. As they share their personal histories, one of the topics that arises is the 1747 Spanish invasion of Beaufort. In book 2, Captured in the Caribbean

, more information comes out about that frightening event.

Although the event isn’t explored in depth in the novel, it was a very real part of Beaufort history. To date, however, no one has really explored the subject of who exactly those Spaniards were who took the town.

That is, until now.

What we already know

In the Preface to Volume 22 of the State Records of North Carolina, we are told that Spaniards invaded the coast in three different locations spanning a period of nearly a decade. The first instance occurred in 1741 near Ocracoke Inlet. The final instance occurred along the Cape Fear when Spaniards invaded Brunswick in 1748. The Beaufort invasion, however, took place in 1747 and is summarized in this way:

In June, 1747, the Spaniards took possession of the town and harbor of Beaufort, and Colonel Thomas Lovick called out his regiment to repel them. Major Enoch Ward was on duty with fifty-eight men when the town was taken on 26 August, and the alarm continued until 10 September, although probably the Spaniards departed earlier. On 6 September William Moore brought in his bill against the public for fifteen hundred pounds of beef for maintaining and imprisoning ten Spanish negroes, and for a gun which had burst in time of action which he said cost him eighty pounds. These Spanish vessels were largely manned by negroes and mulattoes.

At the bottom of this article, there is a list of the brave Beaufort citizens who banded together to fight off these Spanish marauders and restore peace and tranquility to the otherwise quiet seaport town.

Who were these Spanish “negroes and mulattoes” and what did they want?

In The Colonial Records of North Carolina, Volume 4, we are given a bit more information about these men:

In 1747, several small sloops and barcalonjos crept along the coast from St. Augustine, full of armed men, mostly mulattoes and negroes, their small draught securing them from the attacks of the only ship of war then on our coast. They landed at Ocacock, Core Sound, Bear Inlet and Cape Fear, where they killed several people, burned some ships and small vessels, carried off some negroes and slaughtered a great number of cattle and hogs. These practices continued all the summer of 1747, and led to the erection of several forts along the coast, one of which, Fort Johnston, still survives.

Why would “negroes and mulattoes” have “carried off some negroes”?

I can think of a few reasons, but perhaps if we learn who these black Spaniards from St. Augustine were we can better ascertain why they would’ve been interested in taking local “negroes” with them.

Fort Mose — The Spaniard’s Gambit?

Established in 1738 as the first free black settlement in what would eventually become the United States, Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, or “Fort Mose” (pronounced Moh-say) for short, was located just outside St. Augustine, Florida. It was created as a Spanish sanctuary of sorts for runaway slaves from the Carolinas. They were welcome to stay in the settlement as free men and women provided they would convert to Catholicism and pledge their allegiance to the King of Spain.

It should be pointed out that their allegiance meant that their position just north of St. Augustine demanded the residents of Fort Mose act as the northern defense for America’s oldest city, a challenging position considering Spain’s enemies to the north were the English.

Just two years later, in 1740, their allegiance was put to the test when British forces came from Georgia, led by James Oglethorpe, with the intention of taking over the fort. Spanish troops, along with local Indians and the free black militia counterattacked and ran the British troops out, but destroyed the original fort in the process. For a time, the residents of Fort Mose relocated to St. Augustine and lived among the Spanish there, but it wasn’t to last.

In his book, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, historian Ira Berlin writes:

In his book, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, historian Ira Berlin writes:

Declaring themselves “vassals of the King and deserving of royal protection,” they continually put themselves in the forefront of service to the Crown with the expectations that the Crown would reciprocate.

Hoped-for rewards were not always forthcoming. All “vassals of the King” were not equally favored. Beginning in 1749, a new governor of Florida forced black people to return to Mose, much against their will, as they had enjoyed the cosmopolitan life of St. Augustine, where their ability to converse in several European, Indian, and African languages gave them a place as cultural brokers in a multicultural society.

Make no mistake about it, mercy and compassion are not what prompted the Spanish government to welcome fugitive slaves into the Florida colony. It was a strategic decision. What better way to destabilize the fledgling English colonies to the north than to entice their labor force—albeit their slave labor force—to run south? And then, on top of that, they expected those slaves-turned-settlers to take up arms against any threats to Spain and her territories.

Maybe even return to the colonies from whence they came to take their countrymen and exact a bit of revenge?

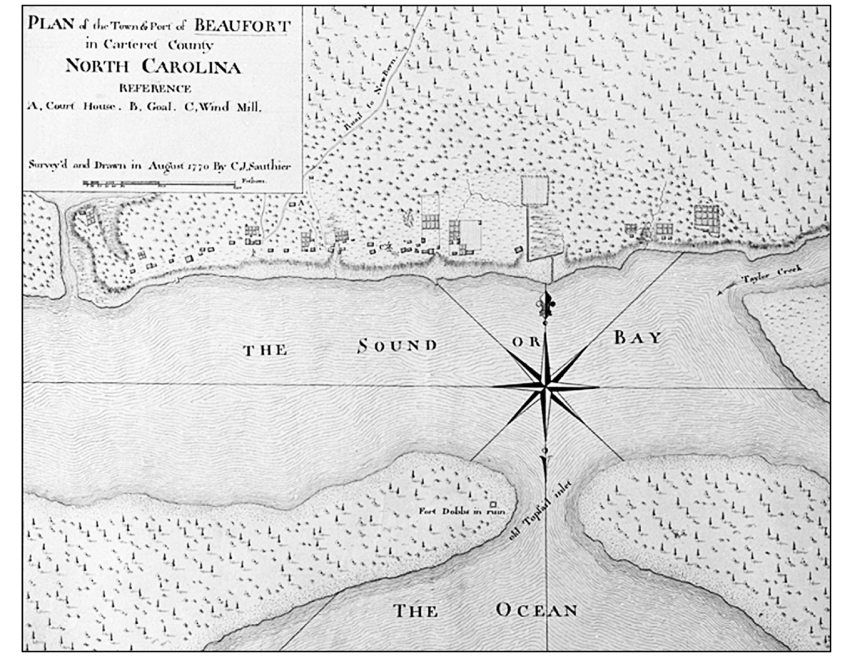

Why was Beaufort a target?

As it said earlier in this article, the attack on Beaufort was one of a series of attacks on the coast of North Carolina by Spaniards. Again, it was strategic. According to historian Charles L. Paul, the population of taxables in Carteret County in 1748, the year after the invasion, was only 320, while the taxables for the town of Beaufort was only one-tenth of that number, or just 32. (In North Carolina, taxables, or tithables, were defined as follows, “…every white Person Male of the age of Sixteen Years and upwards all Negroes Mulattoes Mustees Male or female and all Persons of Mixt Blood to the fourth Generation Male and Female of the age of twelve years and upwards, and no other Persons whatsoever, shall be deem’d Tithables.”)

In other words, Beaufort would’ve been seen as a point of weakness in the colony. Spanish attacks weren’t launched on the more populous areas.

Since the report said, “they killed several people, burned some ships and small vessels, carried off some negroes and slaughtered a great number of cattle and hogs,” it’s entirely possible that the purpose of the attack was to either free or take slaves and generally create mayhem, weakening the town by destroying property.

North Carolina didn’t have any great ports like Charleston. The ports that did exist in the colony were critical to its success. By launching attacks at various points along the coast, the Spanish invaders were proving their allegiance to the King of Spain by attacking his enemies in the English colony and perhaps enjoying a bit of indirect revenge on the Carolinas where they, or their forebears, had originally been enslaved.

What became of the free blacks of Fort Mose and St. Augustine?

Most of the black population of Fort Mose and St. Augustine ended up accompanying their Spanish compatriots to Cuba after Florida was ceded to the British with the Peace of Paris in 1763. (Britain temporarily had control of Havana—for nearly one year from 1762 to 1763—until they agreed to give it back to Spain in exchange for East Florida. West Florida was already under British control.)

According to Berlin, while the the black population at St. Augustine and Fort Mose totaled about 3,000, only about a quarter of them were free. While the National Park Service has called Fort Mose a precursor site to the Underground Railroad, a full three-quarters—totaling over 2,000 souls—of the black inhabitants of this “free black settlement” were enslaved.

It’s even possible that the “negroes” taken during the raid on Beaufort were, themselves, brought into slavery in Florida.

Who were the men who fought off the Spanish marauders?

Thanks to the wonderful documentary work of Joel S. Russell, we have a great deal of Carteret County historical and genealogical information available online at his website. He has lists for four key dates involving Beaufort’s history with the Spanish invasion. The first, June 14, 1747, was when Spanish ships were out in the bay taking ships. The second, August 26, 1747, was the day the Spaniards took Beaufort. The third date, September 1, 1747, was when our expanded militia began to fight off the marauders. By the fourth date, September 10, the attack on Beaufort was over.

Private John Arthur

Private Thomas Austin Jr

Private Thomas Austin Sr (This is my 7th-great-grandfather!)

Sergeant George Bell

Private James Bell Jr

Private John Bell

Private Newell Bell

Private Ross Bell

Private William Bowen

Private John Brown

Private William Burn

Private Cornel Canaday

Private Richard Canaday

Sergeant Thomas Canaday

Private Daniel Catholick

Private Ephraim Chadwick

Captain Charles Cogdell

Private George Cogdell

Private John Cogdell

Ensign Richard Cogdell

Private William Cole

Private Joseph Davis

Private William Dennis

Private Daniel Everitt

Private Joseph Fulford

Private Joseph Fulford Jr

Lieutenant Edward Fuller

Private Richard Gabriel

Private Dederick Gibble

Private Thomas Gillikin

Private Thomas Gillikin Jr

Private Benjamin Guthrie

Private Benjamin Hancock

Private Nathaniel Hancock

Private David Hicks

Private Samuel Howland

Private Ambrose Jones

Private David Lewis

Private Thomas Love

Private John McDowell

Private Jobe Meders

Private Timothy Merryhew

Private Joshua Nash

Private Samuel Negus

Private George Neithercott

Private Elias Nelson

Private John Nelson

Private William Owen

Private Nicholas Pacquinett

Private Isaac Parker

Private Peter Piver

Private Robert Polk

Private Robert Potts

Private Laughlin Quin

Rgt. Clerk George Read

Private Daniel Rees

Private John Roberts

Private William Roberts

Private Daniel Ross

Ensign John Shackleford

Private John Shackleford

Private David Shepard

Private Edward Shepard

Private Cornelius Simpson

Private Edward Simpson

Private John Simpson

Private Joshua Simpson

Private Benjamin Small (and son)

Private William Taylor

Private Richard Thompson

Private Resolve Waldron

Major Enoch Ward

Private Richard Ward

Private Valentine Ward

Private Jonas Weeks

Private Lewis Welsh

Private Maddock Wharton

Private Samuel Whitehurst

Private John Williamson

Private Richard Williamson

Sergeant John Williston

Private John Williston

Private Thomas Williston

Private James Woodland

The Annual Beaufort Pirate Invasion

Beautiful historic Beaufort, NC is a town that loves its history — both real and imagined — and in 1960, the first ever re-enactment of the Spanish invasion took place as a way of commemorating the victory of the Beaufort militia over the attacking Spaniards.

Beaufort artist, author, and historian extraordinaire, Mary Faith Warshaw, has a very thorough article on the history behind the original Spanish invasion as well as a summary of the re-enactments in 1960 and 1961.

These days, an event known as the Beaufort Pirate Invasion has taken things into a slightly different direction, bringing in Pirate re-enactors from all over the country to spend two days acting out scenes that are more reminiscent of the Golden Age of Piracy (or Pirates of the Caribbean) rather than the 1747 Spanish attack.

While the contemporary festivities aren’t strictly a re-enactment of what happened in that frightening summer of 1747, it’s still a wonderful event of great fun that will hopefully get folks interested in learning about the real history of the town and the region.

(This article was originally published April 14, 2015.)